Abstract

Stonehenge, the iconic Neolithic monument on Salisbury Plain, continues to captivate archaeologists through innovative analytical techniques and interdisciplinary approaches. This review synthesises major publications from 2025 and early 2026, focusing on themes of stone sourcing, transport logistics, landscape archaeology, palaeoenvironmental reconstructions, astronomical alignments, and non-invasive methods for detecting hidden features. Key findings reinforce human agency in the monument's construction, highlighting extensive prehistoric networks, ritual complexities, and environmental interactions. Debates on sarsen provenances and glacial theories persist, while advancements in digital modelling address challenges like lichen obscuration. Collectively, these studies enhance our understanding of Stonehenge's role within broader Neolithic and Bronze Age societies.

Introduction

Stonehenge's enduring mystery has spurred a surge in research, particularly in 2025, leveraging advanced technologies such as isotope analysis, geophysical surveys, and machine learning. This article consolidates insights from recent peer-reviewed papers, emphasising deliberate human efforts in stone procurement and placement, while dispelling naturalistic explanations like glacial transport. Sections are organised thematically: bluestone and sarsen sourcing, faunal evidence, landscape features, palaeoenvironmental contexts, astronomical observations, and methodological innovations for carvings. The review draws on publications up to January 2026, reflecting the dynamic pace of discoveries.

Bluestone Sourcing and Transport: Rejecting Glacial Hypotheses

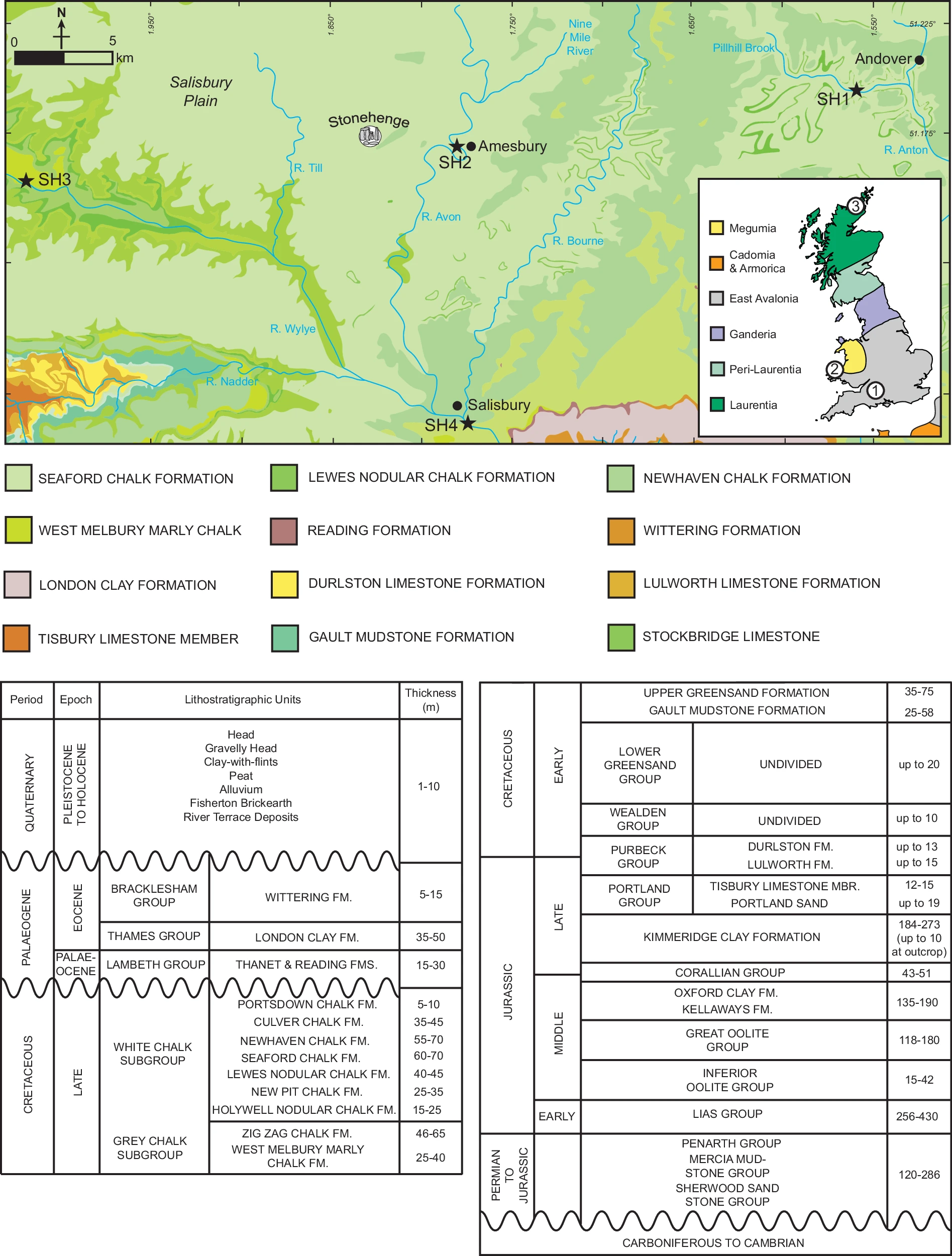

A cornerstone of 2025 research was the re-examination of bluestone origins, firmly attributing their presence at Stonehenge to Neolithic human endeavour rather than Pleistocene ice sheets. A pivotal study analysed the 'Newall boulder', a rhyolite fragment excavated in 1924. Using X-ray, geochemical, microscopic, and surface textural analyses, researchers concluded that the boulder exhibits no glacial erosion signatures, such as striations or polishing. Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports in July 2025, this work provides comprehensive petrological data, supporting intentional transport from Pembrokeshire, Wales, over 200 kilometres.

Complementing this, an early 2026 publication in Communications Earth & Environment employed mineral fingerprinting of over 500 zircon and apatite grains from local river sediments. Led by Curtin University's Anthony J. I. Clarke, the analysis revealed no northern or western mineral signatures indicative of glacial deposition, confirming human movement of bluestones from Wales and potentially Scotland. These findings challenge lingering glacial erratic theories and underscore prehistoric logistical prowess.

Sarsen Sourcing Debates: Geochemical Controversies

Sarsen stones, the massive sandstone uprights and lintels, have been a focal point of provenance studies. A scholarly exchange in Archaeometry highlighted methodological disagreements. In 2024, Anthony Hancock et al. reanalysed data from Nash et al.'s 2020 study, which identified West Woods in Wiltshire as the primary source. Hancock's team critiqued zirconium-normalised trace elements, favouring absolute concentrations and ratios, and proposed alternative origins for stone #58, such as Clatford Bottom or Piggledene, even suggesting possible glacial transport from Scandinavia.

Nash and T. Jake R. Ciborowski responded in 2025, defending their approach by noting Hancock's reliance on weathering-susceptible mobile elements and inadequate handling of intra-site variability. They reaffirmed West Woods using multi-sample statistics, dismissing glacial ideas as geologically implausible. Hancock's subsequent reply upheld their methods, maintaining possibilities of diverse sources. This unresolved debate illustrates the complexities of geochemical sourcing in archaeology.

Relatedly, a January 2025 study in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society examined the Cuckoo Stone and Tor Stone, recumbent sarsens on the River Avon's banks. Portable X-ray fluorescence confirmed origins in West Woods, 20-25 kilometres north, with deliberate placement around 2940–2750 cal BCE, predating Stonehenge's main sarsen phase. Their intervisibility suggests a ceremonial 'portal', integrating Orcadian influences.

Faunal Evidence: Networks and Logistics

Isotopic analyses of animal remains illuminated prehistoric mobility. An August 2025 paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science studied a Neolithic cow tooth from Stonehenge's south entrance. Sequential strontium and lead sampling indicated Welsh origins, aligning with the monument's construction circa 2995–2900 BCE. This supports oxen from western Britain hauling bluestones, evidencing vast networks.

Extending to the Bronze Age, a September 2025 study in Nature Ecology & Evolution analysed isotopes from animal bones in Wiltshire and Thames Valley middens (c. 1000–800 BCE). Pigs dominated, originating from Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, implying long-distance travel for feasts, while cattle and sheep were local. Stonehenge's landscape thus served as a communal hub.

Landscape Archaeology: Pits, Boundaries, and Palaeoenvironments

Geophysical surveys revealed expansive features. A November 2025 article in Internet Archaeology detailed Neolithic pits encircling Durrington Walls, 3 kilometres from Stonehenge. The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project used magnetometry, ground-penetrating radar, and coring to confirm 16 man-made pits forming arcs, dated to the Late Neolithic via chemostratigraphy and ancient DNA. These suggest a massive ceremonial boundary, the largest in Britain.

Palaeoenvironmental work in the Preseli Hills, published October 2025 in Environmental Archaeology, used pollen cores to depict a wooded Mesolithic-Neolithic landscape with gradual pastoral shifts. Cereal pollen from 3000–2200 BCE indicates sustained occupation post-bluestone quarrying.

Astronomical Alignments: Lunar Perspectives

Bournemouth University's project documented the 2024–2025 Major Lunar Standstill, capturing moonrises relative to Station Stones. Observations suggest Neolithic incorporation of lunar cosmology, beyond solar alignments, with publications anticipated.

Methodological Innovations: Detecting Hidden Carvings

A 2025 paper in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (PII: S1296207425001487) employed Difference of Gaussians, pseudo-depth mapping, and MeshNet to identify Early Bronze Age axe-head carvings on Stone 53, discovering 4 new, 10 potential, and 9 reinterpreted ones with 90.7% accuracy.

Addressing lichen obscuration (covering 23% of surfaces), a July 2025 study in Results in Engineering developed lichen simulation and laser scan models to virtually remove Ramalina siliquosa, predicting hidden carvings non-invasively with 73.4% accuracy using adapted MeshNet. A related thesis integrated terahertz spectroscopy for lichen penetration, identifying optimal conditions.

Chronological Modelling

The 2024 Historic England report by Marshall et al. presents refined radiocarbon age models for Woodhenge at Durrington, Wiltshire, utilising Bayesian sequence modelling to date the timber monument's construction to 2635–2575 cal BC (95% probability), with the enclosing ditch and bank following in 2555–2505 cal BC (2% probability) or more likely 2495–2180 cal BC (93% probability), thereby clarifying its phased development and integration with nearby features such as Durrington Walls. Complementing this, Greaney et al.'s 2025 study in Antiquity refines the chronologies for the Flagstones circular enclosure and Alington Avenue long enclosure in Dorchester, Dorset, through 17 new radiocarbon measurements and Bayesian analysis, establishing Flagstones' construction at 3315–3130 cal BC (95% probability) and Alington Avenue predating it by 110–470 years (95% probability), with these dates pre-dating traditional estimates for henge-like structures by up to 285 years and highlighting early innovations in circular monument forms that bridge Early and Middle Neolithic traditions. These revised timelines underscore evolving ceremonial practices and potential connections to broader European networks, prompting a reassessment of monument sequences across the region.

References

Bevins, R.E., Pearce, N.J.G., Ixer, R.A., Scourse, J., Daw, T., Parker Pearson, M., Pitts, M., Field, D., Pirrie, D., Saunders, I. & Power, M.R., 2025. The enigmatic ‘Newall boulder’ excavated at Stonehenge in 1924: new data and correcting the record. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 59, 105303. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105303

Clarke, A.J.I., Kirkland, C.L., Bevins, R.E. et al. A Scottish provenance for the Altar Stone of Stonehenge. Nature 632, 570–575 (2024). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07652-1

Clarke, A.J.I. & Kirkland, C.L., 2026. Detrital zircon–apatite fingerprinting challenges glacial transport of Stonehenge’s megaliths. Communications Earth & Environment, 7(1), pp.1–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03105-3

Esposito, C. et al., 2025. Diverse feasting networks at the end of the Bronze Age in Britain (c. 900–500 BCE) evidenced by multi-isotope analysis. iScience, 28(10), 113271. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.113271

Evans, J.A. et al., 2025. Sequential multi-isotope sampling through a Bos taurus tooth from Stonehenge, to assess comparative sources and incorporation times of strontium and lead. Journal of Archaeological Science, 180, 106269. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106269

Gaffney, V. et al., 2025. The perils of pits: Further research at Durrington Walls henge (2021–2025). Internet Archaeology, 69. Available at: https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.69.19

Greaney, S., Marshall, P., Hajdas, I., Dee, M., et al., 2025. Beginning of the circle? Revised chronologies for Flagstones and Alington Avenue, Dorchester, Dorset. Antiquity. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.28

Hancock, A.J. et al., 2024. Stonehenge revisited: A geochemical approach to interpreting the geographical source of sarsen stone #58. Archaeometry, 67(2), pp.435–456. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12999

Harding, P. et al., 2025. Earliest movement of sarsen into the Stonehenge landscape: New insights from geochemical and visibility analysis of the Cuckoo Stone and Tor Stone. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 91, pp.1–25. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2024.1

Leong, G., Brolly, M. & Nash, D.J., 2025a. Novel approaches for enhanced visualisation and recognition of rock carvings at Stonehenge. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 75, pp.112–121. Available at

SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5126093 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5126093

Leong, G., Brolly, M. & Nash, D.J., 2025b. Novel lichen simulation and laser scan modelling to reveal lichen-covered carvings at Stonehenge. Results in Engineering, 27, 106377. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.106377

Marshall, P., Chadburn, A., Hajdas, I., Dee, M. & Pollard, J., 2024. Woodhenge, Durrington, Wiltshire: Radiocarbon dating and chronological modelling. Historic England Research Report Series 94/2024. Available at: https://historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/94-2024

Nash, D.J. & Ciborowski, T.J.R., 2025. Comment on: ‘Stonehenge revisited: A geochemical approach to interpreting the geographical source of sarsen stone #58’. Archaeometry, 67(3), pp.789–794. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.13105

Parker Pearson, M. et al., 2024. Stonehenge and its Altar Stone: The significance of distant stone sources. Archaeology International, 27(1), pp.113–137. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14324/AI.27.1.13

Silva, F., Chadburn, A. & Ellingson, E., 2024. Stonehenge may have aligned with the moon as well as the sun. The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/stonehenge-may-have-aligned-with-the-moon-as-well-as-the-sun-228133

Spencer, D.E. et al., 2025. Prehistoric landscape change around the sources of Stonehenge’s bluestones in Preseli, Wales. Environmental Archaeology. Advance online publication. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2025.2574741