Stonehenge’s massive

central Altar Stone, a gift from Scotland.

Rob Ixer and Peter

Turner

Dr Rob Ixer indicates the Altar Stone

A new analysis of Stonehenge’s central six-tonne Altar Stone

indicates that it likely to have come from Northeast Scotland, at least 750

kilometres away from its current site in Wessex and perhaps more than 1000

kilometres if it travelled following the present-day coastline. Plate tectonics

and precise radiometric age dating are keys to this discovery.

Almost exactly 60 years ago a series of papers convinced the

geological world that the disputed idea of continental drift was correct, with the

concept of plate tectonics (a continual process of crust being created and

destroyed) being the mechanism for this movement. In the succeeding years the

movements of landmasses since the Proterozoic (2.5 billion years ago) have been

and are being reconstructed (mainly based on palaeomagnetic data) to show

cycles of break-up, coalescence and recombining of super-continents.

Zircon, rutile and apatite are small rare minerals found in

igneous rocks, more so in acidic/granitic rocks than basic/basaltic ones. As

they are chemically inert and quite resistant to weathering therefore

a) they are ideal for obtaining radiometric ages to date

their creation within their parent igneous body;

b) they can be

a significant detrital component in clastic sediments such as sandstone

(recognising that their radiometric age is usually earlier than that of the

enclosing sediment retaining the date of their origins from those landmasses).

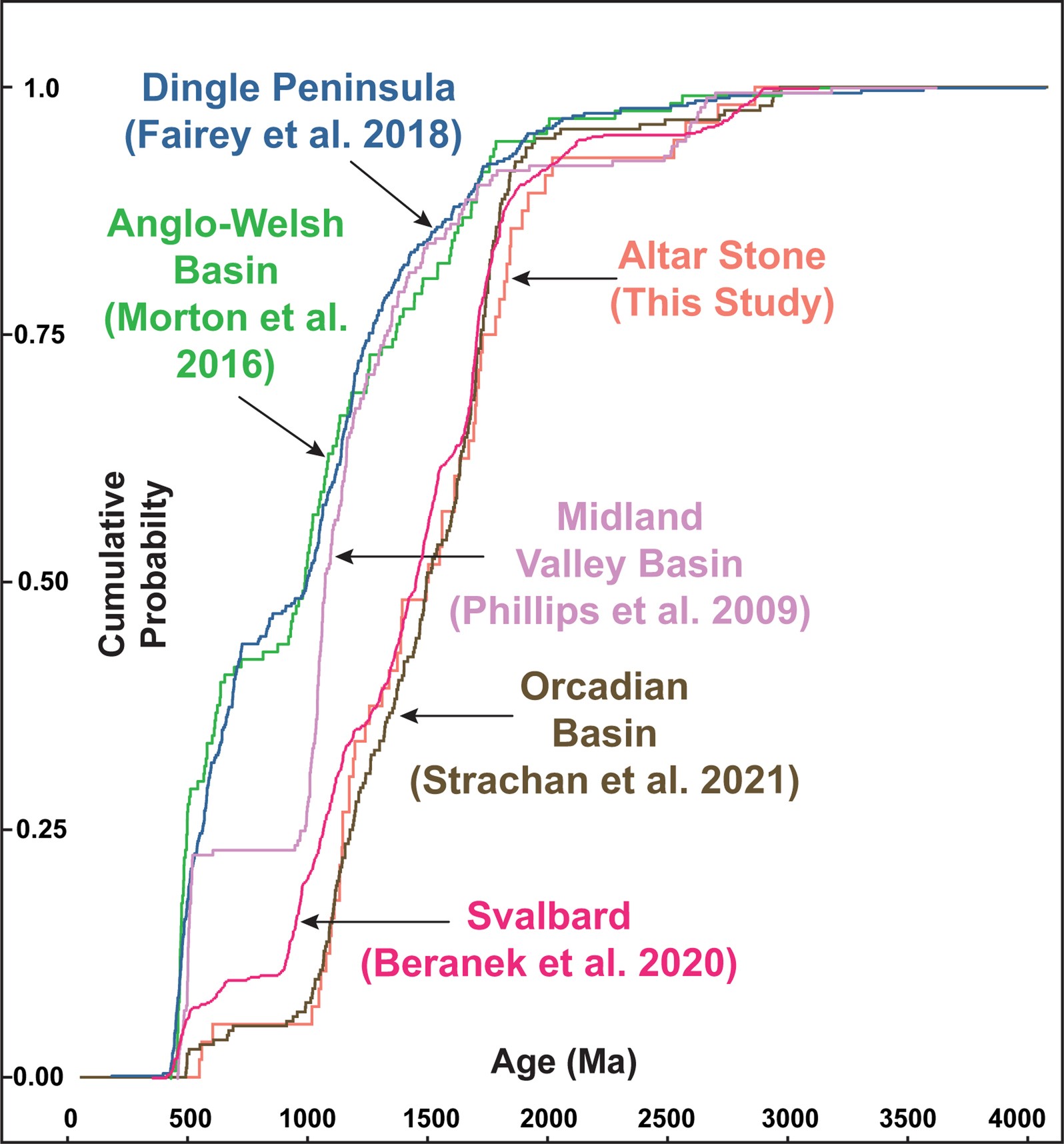

This study, published in Nature, analyses the

chemical and isotopic composition of detrital zircon, rutile and apatite grains

within the Altar Stone – an assumed Palaeozoic Old Red Sandstone - to determine

their isotopic ages and so help to pinpoint the sediment’s origin. An earlier

study in 2023, by a team of eight researchers led by Richard Bevins and

published in the Journal of Archaeological Science demonstrated that the Altar

Stone was not Welsh but probably from northern England and perhaps Scotland:

the authors had noted (in 2020) the presence of a few extremely old and so

intriguing zircons. Quite by chance researchers in Australia contacted the

British Stonehenge research group and were invited to confirm the presence of

these old zircons and to provide additional data. This they have done with

breath-taking results based on uranium-lead and lutetium-hafnium age radiometric

dating from these zircon, apatite, and rutile mineral grains.

It is ironic that every time new researchers are asked to

join and contribute to the Altar Stone studies, from the original duo (Rob Ixer

and Peter Turner) in 2006 to over 12 contributors by 2024, the Altar Stone appears

to move further away from its originally proposed Welsh origin on the banks of

Milford Haven.

The Australian team was able to determine that within the

Altar Stone these detrital grains had a range of ages suggesting their

formation by a number of different igneous events. Some gave Ordovician ages of

between about 470 to 444 million years ago, slightly older than the formation

age of the sandstone. However, mixed in were also grains that were far far

older, greater than 1000 million years which must have been eroded from much

more ancient Archaean rocks. Their ages suggested that these eroded grains came

from an ancient landmass/terrane Laurentia (now forming most of North America

and Greenland) rather than from Ganderia, Meguma or East Avalonia terranes (these

three from north to south, now forming the underlying basement to most of

England and Wales and the Eastern coastal strip of North America). The very old

Altar Stone zircon dates matched igneous

events in Laurentia; events that did not occur in (then) the far distant probable

Gondwanan Ganderia, Meguma, or East Avalonia terranes. Hence, no Old Red

Sandstone sandstones in England and Wales can carry, any Laurentian mineral

grains, as English/Welsh Old Red Sandstone lithologies are essentially sourced

from rocks with non-Laurentian basements.

Tectonic processes slowly (taking almost 100ma) brought

these land masses together. Their join is now marked by the Iapetus Suture.

This is a geological feature that runs roughly along the border between England

and Scotland. It associated with the mountain building event the Caledonian

Orogeny and marks the collision site between Laurentia and Ganderia (with Meguma

and East Avalonia) due to the closure of the Iapetus Ocean and is shown in

figure 1. Parochially but importantly for this study it caused the abutting of

Scotland against England; crucially only British Palaeozoic rocks north of the

Iapetus Suture can show an abundance of Laurentian characteristics, hence the

Altar Stone must be Scottish.

Although more sampling is needed these extraordinary results

(using all of the age dates) suggest that the Altar Stone most closely matches

Old Red Sandstones from the Orcadian Basin which includes both the Orkney and

Shetland Islands plus much of northeast Scotland. These rocks are quite unlike

the Old Red Sandstone of the Anglo-Welsh basin and comprise a thick (2000m+)

sequence of cyclical sandstones, limestones and shales deposited in a large (lacustrine)

lake system. The basin is flanked on all sides by Laurentian basement, and the

sediment was locally sourced, quite consistent with the radiometric dating of

the zircons and other minerals.

Putting aside Merlin’s magic or space alien’s tractor beams,

there are two alternative methods of transport for the Altar Stone: glacial

dumping on Salisbury Plain or physical manhandling by Neolithic people, either

overland or by boat. Despite vociferous, special and cyclical pleading from a

lone living glacial proponent there is no evidence of any glacial erratics on

Salisbury Plain, the nearest accepted glacial deposits that travelled from the

west occur close to the Somerset coastline (but no further) and to the north of

Stonehenge they are more than 100kms distant and carry no Scottish rocks. It

has been anthropogenically moved.

This breath-taking result now raises many archaeological

puzzles, notably how the Altar Stone was transported and more significantly why.

These should be thoroughly formulated before thinking of supplying answers and

choosing one option and are not questions for geologists to answer, for that

would be hubris!, but for archaeologists to solve.

Not Milford Haven but

perhaps Scapa Flow.

Here it might be useful to be reminded of past and present

assertions about the movement of the other Stonehenge bluestones from their

outcrop origins to the Wessex circle.

In 2006 Ixer and Turner with absolute confidence wrote: “A lithologically unremarkable, grey-green,

micaceous sandstone is perhaps the most famous Welsh lithic export in the world

for it is stone 80 (numbering after Atkinson, 1979) namely the fallen ‘Altar

Stone’ from Stonehenge”.

The prevailing almost century old belief was that the Altar

Stone and a companion sandstone now known as the Lower Palaeozoic Sandstone

were collected from the shores of Milford Haven (the exact outcrop for the

Lower Palaeozoic Sandstone on the shore-line was identified by Sir Kingsley

Dunham the leading geologist of the day). They were said to have been transhipped/rafted

from there along the Severn Estuary to Somerset and then punted down rivers to

Salisbury Plain, together with the Preseli bluestones. Major claimed proofs of

this route included dropped/lost bluestones found on Steep Holm and rumoured

orthostats resting on the bottom of Milford Harbour.

In the two decades since, piece by piece, detailed

petrographical and geochemical work has shown all this to be unlikely. The

Steep Holm rocks are nothing like any rock associated with Stonehenge or even

Salisbury Plain, they may even be ship’s ballast; the Altar Stone and Lower

Palaeozoic Sandstone origins are separate and neither is from the Milford Haven

area (the Lower Palaeozoic Sandstone is not Devonian in age but older (Ordovician

perhaps Silurian) and comes from north or northeast of the Preseli Hills); and

the provenanced igneous Preseli bluestones come from the northern slopes of the

Preseli Hills not from its Milford Haven accessible southern slopes. The

current belief is that the Bluestones were manuported overland along a proto-

A40, and it has even been suggested accompanied by a succession of communal

celebrations, (something more difficult to do on the high seas).

How ironic it would be, were the same process needed to be

repeated when dealing with the transhipment of a Scottish Altar Stone.

In 2024 a wiser Ixer and Turner suggest with some confidence

“A lithologically unremarkable, grey-green, micaceous sandstone is perhaps the

secondmost famous Scottish lithic export in the world (after the Stone of

Destiny/Scone) for it is stone 80 (numbering after Atkinson, 1979) namely the

fallen and much travelled ‘Altar Stone’ from Stonehenge”.