By Mike Parker Pearson, Chris Casswell, Jim Rylatt, Adam Stanford, Kate Welham and Josh Pollard

Waun Mawn unfinished stone circle, looking east towards the Preseli ridge. The positions of the circle’s stoneholes, standing stones and marking-out pits are indicated by people standing around the circle’s perimeter

Waun Mawn unfinished stone circle, looking east towards the Preseli ridge. The positions of the circle’s stoneholes, standing stones and marking-out pits are indicated by people standing around the circle’s perimeter

Background

One of the great mysteries of prehistory is why Stonehenge’s ‘bluestones’ came from over 140 miles away in west Wales. While all but two of Stonehenge’s sarsen stones are now identified as coming from West Woods, 15 miles to the north, the smaller bluestones (mostly weighing 1-4 tons) came from the Preseli hills of west Wales. Our aim is to find out why Stonehenge was built of stones from such distant sources.

Over the last ten years, the Stones of Stonehenge project has identified and excavated two of the outcrops from which bluestones were quarried in c.3300-2920 BC, before these megaliths were erected at Stonehenge in its first stage in c.3000-2920 BC. Archaeologists and geologists have hypothesised that Stonehenge’s bluestones might have first been erected as a stone circle in west Wales, that was later dismantled and moved to Salisbury Plain, rather than being brought directly from their quarries.

Archaeological excavations at the partial stone circle at Waun Mawn in 2017 and 2018 uncovered stone holes of two of its four remaining monoliths and revealed 12 further features extending beyond the ends of the arc of monoliths. Six of these were holes for standing stones removed in antiquity. Radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating places their erection at Waun Mawn in 3400-3200 BC and their dismantling before 2120±520 BC (i.e. most likely during the Neolithic).

Together with the four remaining monoliths at Waun Mawn, the six stoneholes excavated in 2018 form part of a former stone circle with a diameter of c.110m. This makes Waun Mawn the third largest stone circle known in Britain. The largest of the stoneholes had an unusual pentagonal-shaped base which can be matched with Stone 62 at Stonehenge and contained

flakes of dolerite that appear to have become detached from the monolith that stood at Waun Mawn; it is of the same type of rock as that of Stone 62 at Stonehenge. Further links with Stonehenge are provided by Waun Mawn’s entrance facing midsummer solstice sunrise and by the diameter of Waun Mawn circle being the same as the diameter of Stonehenge’s perimeter ditch.

Waun Mawn is part of a major ceremonial complex within Preseli, including a Neolithic causewayed enclosure at Banc Du, a Neolithic palisaded enclosure at Dryslwyn, and seven local Neolithic tombs. This provides a new insight into the significance of the source of Stonehenge’s bluestones, and raises interesting new questions about the relationship of this complex with that on Salisbury Plain, such as why some of Stonehenge’s bluestones might have come from one or more previous monuments in Preseli. One of these other monuments might be the smaller (45m-diameter) embanked circle of Gernos-fach, 800m northwest of Waun Mawn.

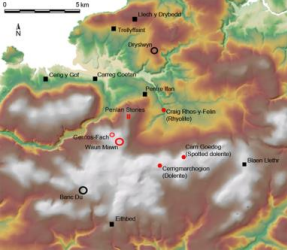

Figure 1. Locations of Waun Mawn, Gernos-fach and other Neolithic sites including dolmens (black squares), enclosures (black circles) and Stonehenge-linked bluestone sources (red dots) as well as Gernos-Fach circle and the Penlan Stones

Research objectives in 2021

The project’s ninth field season continued excavations at Waun Mawn (SN 0835 3398) and began excavations at an embanked circle at Gernos-fach (SN 0770 3452). Geophysical survey at the pair of Penlan standing stones south of Carnedd Meibion-Owen (SN 0901 3575) was also conducted but failed to identify any features other than the two monoliths.

The aims of excavation in 2021 of the incomplete stone circle at Waun Mawn were to: 1. Establish the completeness of this former stone circle, to estimate whether it held more than the 10 standing stones so far detected by their surviving stoneholes. 2. Refine the date of this monument, through further OSL and radiocarbon-dating of materials within its stone holes.

3. Explore the centre of the former stone circle to find out whether this was already a special location when the circle was built and whether a hole survives for a marking-out post to establish the circle’s radius.

The proximity of Gernos-fach to Waun Mawn just half a mile away has raised the possibility that it is of equivalent date to Waun Mawn (i.e. Middle Neolithic) and might have been similarly dismantled in prehistory to provide bluestones for Stonehenge.

The aims of the 2021 excavation of Gernos-fach embanked circle were to: 1. Establish when and how it was constructed.

2. Establish whether its encircling bank originally held a number of standing stones and, if so, when these were removed.

3. Establish the positions and forms of the circle’s entrances and whether they were oriented towards significant astronomical alignments.

Waun Mawn: an unfinished and dismantled stone circle

Excavation of the centre of Waun Mawn’s circle revealed the presence of a fireplace within a small bowl-shaped hearth located 0.70m from the circle’s precise centre (as estimated in 2018). Although this was not the hypothesised hole for a marking-out post (see aim 3 above), it is potentially far more significant in that the wood charcoal in its fill may provide an even more secure and precise date than that already obtained for the circle’s construction. The hearth was covered by disturbed sediment from the fall of a large tree. This raises the possibility that this tree was the visible marker at the circle’s centre, from which its radius of 55m was measured. As a potentially long-lived landmark, the tree – likely to be isolated and prominent, given the lack of evidence for similarly large trees across all the Waun Mawn trenches – could have been an enduring feature in the prehistoric landscape. The variable distances from this central point to the stoneholes – up to 5m in some cases – imply that measuring was conducted by pacing rather than with a rope of fixed length.

Excavations around the circle’s perimeter confirmed that two extensive arcs in the south and west had been largely or entirely devoid of stoneholes for since-removed standing stones. While there was no further trace of any features on the west side, the southern arc produced a further three or possibly four features which followed the circle’s circumference but had never held standing stones. These are interpreted as marking-out pits for standing

stones that were never erected. Two of them, when viewed from the centre of the circle, are aligned on Carn Goedog (a bluestone quarry) and Foel Feddau (a summit on the Preseli ridge). This suggests that their positioning within the circle’s perimeter was sighted through from the centre. An additional such ‘marking-out’ pit on this southern arc was excavated in 2018 and dates to the period of the circle’s construction.

Figure 2. The hearth at the centre of Waun Mawn stone circle, excavated by Geraint Lloyd

Figure 2. The hearth at the centre of Waun Mawn stone circle, excavated by Geraint Lloyd

On the east side, a new stonehole was found in 2021, forming the eastern end of an arc of four surviving standing stones and six additional stoneholes that extends for almost 100m from the furthest of these in the circle’s northwest. The presence of a ‘marking-out’ pit just 9m from the eastern terminal of this arc suggests that it was at this very point that construction of the circle was abandoned.

Figure 3. The ‘marking-out’ pit beyond the last stonehole in the eastern arc, indicative of the stone circle’s non-completion (the two small holes within the pit are the result of OSL sampling)

Figure 3. The ‘marking-out’ pit beyond the last stonehole in the eastern arc, indicative of the stone circle’s non-completion (the two small holes within the pit are the result of OSL sampling)

Reinvestigation of the small recumbent stone forming the left hand side of the midsummer solstice-oriented entrance revealed that the pit identified in 2018 as its stonehole was in fact a later feature cut against the west side of the stone’s original stonehole. An interesting discovery here was a posthole directly adjacent to the northeast end of the stonehole. Together with a similar posthole detected in 2018 in the southwest end of the stonehole forming the right side of this entrance, the posts provide evidence for laying out the midsummer solstice-facing entrance with posts. Presumably this was done before the standing stones were erected though only the right hand stonehole preserved evidence that the posthole was inserted before the stonehole. These are the only two stoneholes, out of ten excavated instances, with accompanying postholes.

Figure 4. The posthole (right) and stonehole for the stone (top right) originally forming the left hand side of Waun Mawn’s midsummer solstice sunrise-facing entrance

Figure 4. The posthole (right) and stonehole for the stone (top right) originally forming the left hand side of Waun Mawn’s midsummer solstice sunrise-facing entrance

The only stoneholes detected outside of the circle’s northwest to eastern arc were two on its southwest perimeter. One of these was excavated in 2018 and a second one, 5.5m to its west, was investigated in 2021. This proved to be the only stonehole at Waun Mawn found to have been filled immediately after its standing stone was withdrawn. Its empty socket was filled with two layers of sediment, the upper one containing a stack of flat stones that formed a sturdy base for a large dolerite slab laid on top of it and whose lip extended over the top of these flat stones. Like all other stoneholes at Waun Mawn, this one’s ramp lay on the side opposite the centre of the circle, indicating that the standing stone had been extracted in that direction. The position and secure bedding of the large slab would have enabled it to be used as a rigid fulcrum to lever out the base of the standing stone once it had been toppled. Its imprint in the bottom of the pit revealed this to have been a substantial monolith, 0.45m-0.50m in basal cross-section.

Excavations to either side of this pair of stoneholes in the southwest revealed no further stoneholes, suggesting that they formed an isolated pair. Viewed from the centre of the circle, they align not to midwinter solstice sunset (to the east of them) but to where the sun

sets a month or so before and after midwinter. They do not appear to mark or frame any significant topographic feature on the horizon.

Figure 5. The large slab placed over the top of a stonehole on the southwestern perimeter of Waun Mawn stone circle

On and around the position of midwinter solstice sunset along the circle’s perimeter, a concentration of stone tools included artefacts of flint (four scrapers, an oblique arrowhead, a serrated knife and six flakes) and quartz (eight flakes and two cores), a large dolerite flake and a circular, trimmed mudstone disc. Near the centre of this concentration, a small setting of flat stones may be the remains of a humanly-made structure. The oblique arrowhead is of a type in use in Britain between 3400 BC and 2400 BC. Other finds from around the circle’s perimeter consisted of two circular discs and a quartz core in the east, a quartz bifacial knife in the south and a flint blade in the west.

Figure 6. An oblique arrowhead from the southwest perimeter of Waun Mawn stone circle

In summary, the 2021 excavations provide evidence that only 30% of Waun Mawn’s stone circle was ever completed, leaving large gaps on the west and south sides. Features along the southern perimeter can be identified as holes that were dug but never held stones, revealing that building of the circle stopped in mid-construction. Eight standing stones were subsequently dismantled, leaving just four in place. It is unlikely that there were ever more than 17 stones erected within this circle, resulting in between eight and 13 being taken away in prehistory. It is possible but unlikely that there was another dismantled circle within the larger, 110m-diameter circle; early stone circles of this type, such as Stanton Drew, tend to have smaller circles beyond them and not inside them. In these circumstances, if Waun Mawn provided some of the bluestones for Stonehenge, these can only have been a small portion of the total.

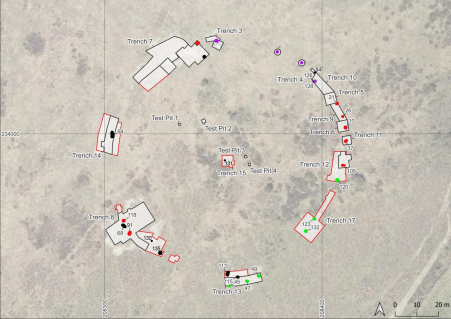

Figure 7. Plan of trenches (black lines 2017-2018; red lines 2021) showing stoneholes (red), remaining stones (purple), pits (green) and other features (black) excavated at Waun Mawn

Gernos-fach: an embanked stone circle

Half a mile to the northwest of Waun Mawn, excavations at Gernos-fach, an embanked stone circle 45m in diameter, consisted of three trenches. The main one was positioned on the circle’s dilapidated eastern bank, with smaller trenches over the northern part of the bank (where the bank was better preserved) and within the circle’s centre.

Figure 8. The three trenches at Gernos-fach embanked stone circle during deturfing. North is to the left

Figure 8. The three trenches at Gernos-fach embanked stone circle during deturfing. North is to the left

The circle’s enclosing bank contained two dolerite standing stones, one of them leaning and the other small and stumpy. Whilst the stumpy stone is probably a late addition, inserted as part of a medieval rectangular structure possibly the remains of a sheepfold, the leaning stone may well be an original element of the circle though it could have been re-set and its packing fills disturbed. This unspotted dolerite pillar, over 2.10m long, is unweathered on one side, likely to be the result of its lying on the ground before erection; it is not a quarried monolith like so many of the bluestones. Its relationship to the bank could not be determined with certainty because of erosion of the bank around it. However, about 5m to its north lay an empty stonehole, also positioned centrally beneath the spine of the bank. This had held a standing stone before the bank was constructed. This eastern arc of bank had been robbed of much of its stone, quite probably in the medieval period, leaving a layer of sediment and stones that sealed the stonehole. The fill of this stonehole’s empty socket was loose and similar to the bank material, raising the possibility that its standing stone was extracted at the same time that the bank was robbed, though this remains to be determined by OSL and radiocarbon dating. The standing stone had been pulled out from the east, away

from the centre of the circle, and its imprint showed that the size of the stone that once stood here was about 0.80m x 0.50m in basal cross-section. This compares closely with the basal dimensions of Stone 46 at Stonehenge, a rhyolite of Group F, the outcrop source of which has not yet been identified.

Figure 9. The empty stonehole (foreground) and leaning stone (background) at Gernos-fach, viewed from the north

Figure 9. The empty stonehole (foreground) and leaning stone (background) at Gernos-fach, viewed from the north

The bank was constructed of small stones and soil, the larger slabs being placed on or towards the top of the bank. This process of construction is different to that observed for field clearance cairns and walls where the larger stones are towards the base. A ragged line of slabs along the bank’s inside edge may be the remnants of an inner kerb, displaced by later activity, perhaps stone-robbing when the medieval structure was built. There was no sign of an entrance in the north or northeast, as suggested on the surface prior to excavation, but geophysical survey has revealed a possible access in the south, an area heavily disturbed by later (presumably medieval) activity.

In all three trenches there were traces of cobbling across the interior of the circle. This reached the eastern and northern edges of the interior and covered the centre except for a raised area which extended beyond the edges of the central trench towards the southwest of the circle’s interior. Around this raised area, the cobbling exhibited evidence of sustained footfall.

Finds from the enclosing bank consisted of a flint flake, two quartz scrapers, nine quartz flakes, six quartz cores, a large knife of igneous rock, two stone flakes, a chert spall and eight trimmed mudstone discs of varying degrees of circularity. None of these artefacts are necessarily diagnostic of the monument’s date which is likely to be in the range between

Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. Radiocarbon and OSL samples were taken to see if the monument’s different phases can be dated.

Artefacts deposited on top of the bank included a medieval horseshoe, a sherd of medieval Dyfed gravel-tempered ware and a sherd of Roman pottery.

Circular, trimmed mudstone discs are also known from Waun Mawn stone circle and from Neolithic levels at Carn Goedog bluestone quarry. Their purpose is unknown but they are regular finds on Neolithic sites in western and northern Britain where they are usually interpreted as ‘pot-lids’. In continental Europe they are also found in Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age burials where they can be identified as plates on which to place tinder for making fire. Their purpose here in Preseli is, however, unknown – they might simply have been no more than playthings, shaped to while away the time. Some are carefully executed whereas others have received only the most casual working.

Figure 10. A trimmed mudstone disc (SF132) from the eastern perimeter of Waun Mawn

In summary, the 2021 excavations at Gernos-fach uncovered a stonehole for a removed standing stone. The large leaning stone may be another in what may well have been an original stone circle. Further excavation will reveal whether further stoneholes remain to be discovered beneath the bank. The plan of this embanked circle is similar to that of Meini Gwyr at Glandy Cross; that circle was smaller (37m in diameter) and retained its 17 standing stones until the historical era. In comparison, the Gernos-fach stonehole raises the possibility that this site too once sported a ring of standing stones that could have numbered as many as 24 or so.

Figure 11. Plan of trenches and features (black) excavated at Gernos-fach

Figure 11. Plan of trenches and features (black) excavated at Gernos-fach

Acknowledgements

We thank the landowner, Alexander Hawkesworth, and the land agent, Kathryn Perkins for permission to excavate at Waun Mawn and Gernos-fach. Permissions were also obtained from Natural Resources Wales and the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park. Among the staff of PCNP, Tomos Jones and Richard Vaughan deserve a special mention for their help and advice. We are also very grateful to Lyn and Gwyndaf Rees for on-site help and support. Simon Turner kindly arranged an evening lecture at the Bluestone Brewery.

Supervisors were Chris Casswell, Jim Rylatt, Duncan Schlee and Jason Tyler. Specialists were Richard Bevins, Adam Stanford, Tim Kinnaird, Clive Ruggles and Ellen Simmons (assisted by Dave Cooper).

Volunteers were Louise Austin, Victoria Barker, Michael Bissmire, Emma Brooks, Anne Chambers, Ian Chambers, Stephen Cogbill, Clare Dow, John Dow, ffi Draper, Dave Durkin, Stewart Eves, Louis Falkingham, Barney Harris, Michael Holt, Robert Hopkins, Hayley Hughes, Rebecca Hyde, Aled Jenkins, John Jenkins, Jake Keen, Jason Lawday, Geraint Lloyd, Stella Maddock, Michael Marshman, Lucy Mills, Ceri Owen-Jones, Richmond Pike, Ginny Pringle, Edward Puckett, Becca Pullen, Martin Rose, Mike Standish, Julian Stanton, Anne Teather, Julie Till, Mike Tizzard, Zoe Walsh, Jude Walter, Rob Walter, Jack Whitney, Joan Wilks, Andy Williams, Howard Williams, Moira Williams, David Wilmshurst, Eponine Wong, Xinyi Xie and Barbara Young.