Songs of the Stones: An Investigation into the Acoustic Culture of Stonehenge

Dr. Rupert Till - University of Huddersfield, UK. Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music doi:10.5429/2079-3871(2010)v1i2.10en

"concludes that the sonic features of Stonehenge were noticeable and significant, and that it is likely that they were a part of the ritual culture of the site."

Now acoustic expert D.N.Thomas has hit back -

Pseudo science in British archaeoacoustics: Rupert Till's interpretation of the perception of sound.

which "suggests that Till's approach is pseudo scientific approach and likely to

lead to erroneous conclusions and misinterpretation".

Pseudo science in British archaeoacoustics: Rupert Till's interpretation of the perception of sound.

D.N.Thomas

'

This essay addresses Rupert Till's interpretation of the human perception of sound in the

paper 'Songs of the Stones: An Investigation into the acoustic culture of Stonehenge' (Till

2010). The author suggests that Till's approach is pseudo scientific and likely to lead to

erroneous conclusions and misinterpretation. Set within the context of an acoustical

analysis of Stonehenge, Till presents his interpretation of the way human beings perceive

audible and inaudible sound in a section titled 'Perception of sound at different

frequencies'. He divides sound into 4 types and outlines the idea as follows,

' From 1-14 hz one perceives frequencies as rhythms, whether a drum pattern or the

rhythmic sound of a train. These frequencies are normally described as a number of beats

per minute or b.p.m. For example 2 Hz equates to two beats per second, or 120 beats per

minute, 3Hz is three oscillations per second, or 180 bpm. Above 3 Hz one typically

subdivides the rhythm, perceiving 4Hz as the same tempo as 2 Hz; as the same speed,

but with a doubled pulse, as 120 bpm with a quaver (eighth note) pulse ... ' (Till 2010, pg

8 ).

Till's ideas are based on his understanding that

' Terms like frequency (Hz) and period (seconds) are useful in different situations, and are

perceived differently, even though they are essentially the same thing' (Till 2010, pg 9).

unfortunately there are serious problems with this interpretation of the term frequency. If

sound is a perception created by vibratory motion of the hearing mechanism and

Sources of sound can be described by displacement time curves ' (Campbell and Greated

1994),

sound analysis indicates that rhythmic frequency (repetition and pulse) measured in hertz

is not comparable to the frequency of a sound wave (wave length and amplitude) also

measured in hertz. A repeated sonic event occurring twice per second creates a periodic

rhythm with a frequency of 2 (hz) but each sonic event results in the creation of a distinct

set of sound waves ranging in frequency from 20-20,000 hz (depending on the nature of

the sound source). It follows that Till's interpretation of the term 'frequency' conflates and

confuses the meaning of that term. The terms 'sound frequency ' and ' rhythm frequency'

are not perceived differently but have distinct meanings. Whilst both rhythm frequency

and sound wave frequency share the common descriptor (Hz), the frequencies of sound

waves cannot be construed as being similar to the frequency of a perceived rhythm.

Professor Rupert Braithwaite warns us of the dangers of the misinterpretation of scientific

concepts,

' Pseudosciences never produce new insightful knowledge, they are circular and static.

Any research that is carried out serves only to establish the pre- existing beliefs or

agendas of the individuals (committing the confirmation - bias fallacy). Here, only certain

forms of information count as knowledge ' ...

Till goes further, his alternative descriptor for the term infrasound as 'Time' leads to a

method in which a number of scientific concepts are confused, conflated and replaced by

a single unworkable approach,

' it is possible to hear notes lower than 20 hz they have to be increasingly loud in order to

hear them... Periodic rhythmic vibrations with frequencies below 20 hz such as a series of

short impulses or clicks, can also be heard ...10 hz can be described as 150 bpm with a

semi quaver pulses or as a time period of 0.1 s (Till 2010 pg 7),

Infrasound (0-20 hz) is not related to or associated with the creation of 'a series of short

impulses or clicks' . Sounds with frequencies below 20 hz are described as inaudible

frequencies because laboratory tests suggest that this is a reasonable conclusion. To think

of infrasound as anything like a rhythmic pulse or beat is highly misleading ( a 2 hz sound

wave is 171 metres long and 42 metres high). Till's approach leads to the conclusion that

Stonehenge has a 'resonant frequency ' of 10 hz, possibly linked to alpha wave patterns.

'Stonehenge could be made to resonate...much like blowing over the top of a bottle to

make it hoot, or like running one's finger around the top of a glass or hitting the skin of a

drum... This would work by making the air in the space vibrate at its fundamental resonant

frequency. Measurements of the diameter of Stonehenge told us that this frequency would

be about 10 hz. ...10 hz is a frequency that when detected in the brain is described as an

alpha wave pattern... ' (Till 2010 pg 7).

Braithwaite warns us of the use and over-reliance on metaphor as an argument in and of

itself. In the paragraph above Till compares the space within a stone circle to that within a

bottle, a glass, and the shell of a drum. The reader is expected to accept understand and

link these metaphors using his peculiar interpretation of the term frequency. Computation

of any fundamental resonant frequency using axial, tangential and oblique mode

calculations is impossible at Stonehenge (the stone 'circle' is open to the sky) such

computation requires an enclosed space (four walls, floor and ceiling). The presentation of

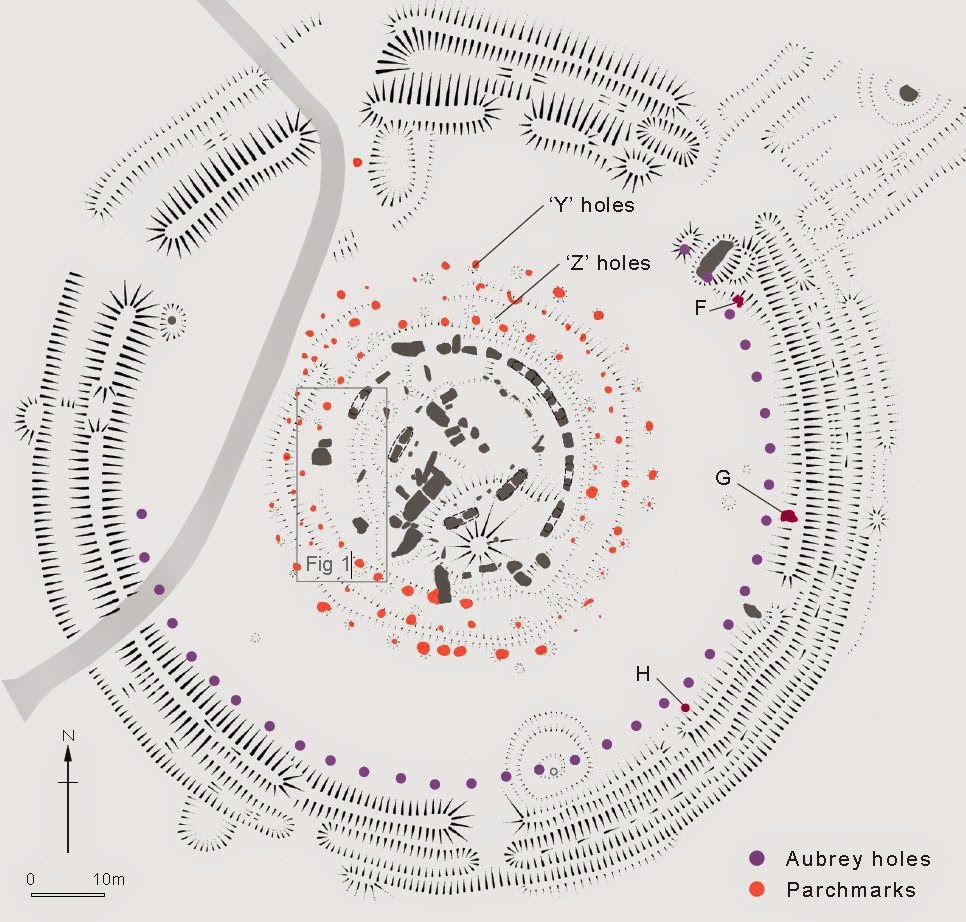

a mathematical model for predicting resonant frequencies (Till 2010 Figure 1 by Faziendi)

at Stonehenge based on the geometry of an open ended cylindrical tube is unhelpful.

Stonehege is not circular in shape. If Stonehenge was an open ended cylindrical tube we

might expect its resonant frequency to be 45 hz but Stonehenge is not an open ended

cylindrical tube.

' At the centre of a circular building... a sound hits and reflects straight back from the

wall ... this would produce a prominent echo and reverberation from the combination of a

number of 'echoes', or reflections …In a circular space.... The overall effect would be

echoes (in a large space) or resonance/ reverberation ' (Till 2010).

Inside a circular building the shape of the walls will be one of many factors (room

dimensions, air gaps, internal structures, surface and building materials) which may

influence the acoustic characteristics of the space. In prehistoric circular dry stone

constructions, bee hive cells, Scottish round houses and circular brochs, sounds do not 'hit

and reflect straight back from the wall' . Inside circular dry stone structures sounds of at

least 1000 hz and upwards are not reflected but scattered, diffused by the edge surfaces

and gaps between the stones. Dry stone construction fosters an acoustically 'dry '

environment with few reflections and short reverberation times (Thomas 2007).

' Pseudoscience presents itself as scientific in nature... the problem here is not only the

false interpretations, but the claims that these interpretations are factual in a scientific

sense. It is this latter inherent claim of scientific credibility and authority which makes the

toxic effect of pseudo thinking so potent. To the uncritical and ill-informed, a pseudo

scientific claim could appear perfectly reasonable' (Braithwaite 2006).

Biography

Braithwaite and Townsend. 2006. Good Vibrations: The Case for a Specific Effect of

Infrasound in Instances of Anomalous Experience has Yet to be Empirically Demonstrated

{Behavioural Brain Sciences Centre, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, UK,

B15, 2TT}http://birmingham.academia.edu/DrJasonJBraithwaite

Braithwaite J. 2006 Seven Fallacies of Thought and Reason: Common Errors in

Reasoning and Argument from Pseudoscience {Behavioural Brain Sciences Centre,

School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, UK, B15, 2TT}

http://birmingham.academia.edu/DrJasonJBraithwaite

Browne, M. N., & Keeley, S. M. (2003) Asking the right questions. A guide to critical

thinking (7th Edition), New Jersey. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Campbell M. and Greated C. 1994 The Musician's Guide to Acoustics. Oxford. Publisher.

Oxford University Press. ISBN 019159167X, 9780191591679

Carroll, R. T. (2005) Becoming a critical thinker. A guide for the new millennium (2nd Ed).

Boston. Pearson Custom Publishing.

Carroll, R. T. (2003) The skeptics dictionary. A collection of strange beliefs, amusing

deceptions and dangerous delusions. New Jersey. John Wiley & Sons,

Gardner, M. (1957) Fads and fallacies in the name of science. New York. Dover

Publications, Inc. Oxford 2010.

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/conflate

Till R 2010 'Songs of the Stones : An Investigation into the acoustic culture of Stonehenge'.

http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/13248/1/TillSongs308-2422-1-PB.pdfBraithwaite, J.J. (2006)

Lett, J (1990) A field guide to critical thinking. Skeptical Inquirer (14), 2, 1- 9.

Shermer, M. (2002) Why people believe weird things. New York. Henry Holt & Company.

Thouless., R. H. (1968) Straight and crooked thinking. London, Pan Books.

Thomas 2007. An Investigation of Aural Space inside Mousa Broch by Observation and

Analysis of Sound and Light.

http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue30/thomas_index.html

Whyte, J. (2005) Crimes against logic. New York. McGraw-Hill.