A new study published in The Antiquaries Journal offers fresh insight into how prehistoric communities may have shaped sarsen, the coarse-grained sandstone that forms Stonehenge’s iconic monoliths. In “Demystifying Sarsen: Breaking the Unbreakable,” Phil Harding, FSA, of Wessex Archaeology, applies an experimental approach to understand how Neolithic craftspeople worked this notoriously durable silicate. “This small project was initiated to create a broader understanding of the working properties of sarsen and its challenges,” Harding explains, noting that direct percussion offers “the potential provided by shock waves to split and shape this intractable silicate successfully and repeatedly.” Supported by the Society of Antiquaries of London, the research builds upon earlier theoretical models by Gowland and others to provide practical observations relevant to prehistoric stoneworking.

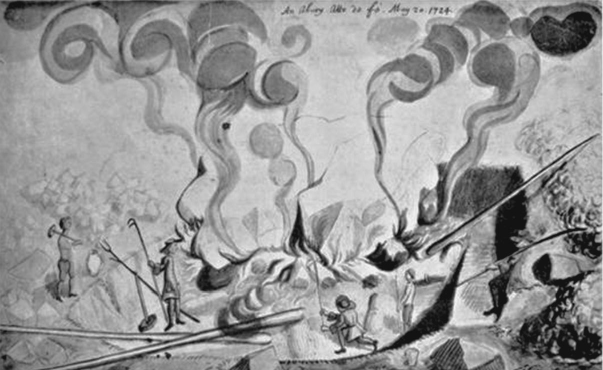

Using a single 54kg block of saccharoidal sarsen, Harding tested the processes of splitting, flaking, and pecking through controlled experiments. Hammers comparable to prehistoric tools—including flint and quartzite examples, a ball pein hammer, and a 3kg sledgehammer—were employed to assess fracture mechanics and the effects of heat. The results show that repeated, accurate blows using direct percussion could progressively open controlled fractures, adapting methods familiar from flint knapping. Flaking produced broad trimming flakes but proved “unsuited for thinning or shaping monoliths,” while peck dressing, though effective, was laborious and slow. Heating the stone to around 400°C offered no advantage, and higher temperatures “shatter the structure of sarsen, rendering it unworkable.”

The findings suggest that controlled splitting by percussion was the principal technique for reducing large sarsen blocks, with flaking and pecking serving more limited roles in finishing surfaces. Harding concludes that while the experiments cannot “comprehensively resolve the complex technological challenges linked to this stone,” they “reawaken understanding and appreciation of the potential provided by direct percussion” and “admiration for the skill and persistence of the prehistoric workers in the process.” Together, these results strengthen the case that Neolithic builders of Stonehenge relied on carefully applied shock and precision rather than wedges or heat to master the “unbreakable” stone.

Harding, P. (2025) ‘DEMYSTIFYING SARSEN: BREAKING THE UNBREAKABLE’, The Antiquaries Journal, pp. 1–21. doi:10.1017/S0003581525100309.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome on fresh posts - you just need a Google account to do so.