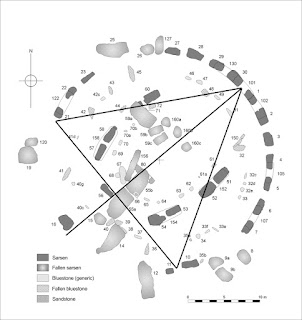

On January 3, 1797, an entire trilithon, stones 57,58,158, collapsed at Stonehenge. The trilithon was re-erected in 1958.

"The desire to do something about the state of Stonehenge seems first to have been discussed in the wake of the collapse of a trilithon in January 1797 .During 1800, the Rev. William Coxe, Rector of Stourton, managed to raise some £50 by subscription to go towards the cost of putting the collapsed stones back up again. The owner of Stonehenge at the time, the 4th

Duke of Queensbury, refused permission. Chippindale (2005, 115) described the Duke as ‘notoriously mean and unpredictable’, and mentioned his serious neglect of Amesbury House as evidence. However, a near-contemporary account of a subsequent request to re-erect the stones suggests that Queensbury’s refusal may have been rooted more in aesthetics than meanness.The antiquarian Thomas Stackhouse’s reference to the Duke came in his account of a further effort to raise the collapsed stones. The date of this attempt is unclear, but must have occurred prior to 1810, the year the Duke died. Stackhouse described the events in his

Two Lectures on the Remains of Ancient Pagan Britain..., published in 1833:

“In contemplating the lofty and weighty masses of Stonehenge, many people conclude that the ancient Britons possessed a knowledge of the mechanical powers, or the combination of them, superior to that of the moderns; this can only be the conclusion of those who are totally unacquainted with the present state of mechanical science in this and the neighbouring countries... About eight years ago, a gentleman of Salisbury, one of a small association of antiquaries, of whom the learned and persevering Sir R. C. Hoare may, I believe, be considered a member, very obligingly, drove me to Stonehenge. In our way thither he informed me that these gentlemen and himself being determined to give the world a practical confutation of the error, agreed to send for a person from London to survey the spot and give an estimate of the charge for re-erecting three of the fallen stones, that is, one entire trilithon; they did so: after duly considering the matter, the person applied to, agreed to raise the uprights, and replace the top stone for £300; this,he told me, they were willing to give him, and would have done it, but it was necessary to have permission from the lord of the manor, (the late Duke of Queensbury,) on applying to him for the purpose, he declined giving his consent by saying, that he thought the whole more picturesque in its present state, and desired that, on that ground, they would excuse him”. "

In 1802 William Cunnington who mainly worked for Sir Richard Colt Hoare excavated at Stonehenge and that may be the year that the plan to re-erect the stones was discussed as above.

In 1802 a J.Day and W.Law Masons (from) Camberwell carved their names on the back of Stone 56.

John Day was a Stonemason in Camberwell and I think his

firm still survives to day But as well as being being a successful Stonemason he also was an inventor and registered a couple of patents which suggest he would have had the interest and skills to work at Stonehenge.

"John Day, of Camberwell-green, in the parish of St. Mary, Lambeth, stone-mason; for an engine for the purpose of loading and unloading vessels, and also for raising large anchors and other immense weights to any height required. Dated February 12, 1807."

So it seems likely that the "person from London" who quoted £300 to re-erect the trilithon was John Day of Camberwell who left his mark behind. Maybe the Duke wasn't pleased and that is why the project never proceeded.